Read Part 1 of “The Lost League” here…

In 1979, Mike Dowler languishes as the reserve goalkeeper for Newport County in the fourth division of British football. Keepers are supposed to be giants, but Dowler stands 5’9 (don’t listen to the jokester on Wikipedia who listed him as 5’0). Managers want a lad with some height.

“I’m as big as this. That’s it!” he says cheerfully.

But Dowler doesn’t blame his height for his lack of success at Newport County.

“I had my shot, and I didn’t take it. Not ability…what held me back was confidence,” Dowler says.

Fortuitously, Wichita Wings player/assistant coach George Ley comes over from America to scout players in his native UK. Ley catches a game in Wales and figures Dowler will be perfect for indoor play, where height isn’t as vital.

The Wings fly Dowler across the Atlantic for a tryout. The captain comes on the intercom to announce the flight will take just under eight hours. Jesus Christ, where are we going? It must be uphill all the way, he thinks. As his initial flight approaches Chicago, the city stretches out for an eternity. Good grief, this is bigger than Wales! On the plane to Wichita, Dowler tells the man next to him that he’s here to play professional “football.” Confusing sports, the man notes that Dowler isn’t very big for a football player.

“I’m not very big for a soccer goalie either,” he replies.

Though the tryout is successful, it might have been Newport County all over again if not for Van Eron’s knee troubles. But Bob’s-your-uncle, and Dowler is, temporarily, the starting goalkeeper for the Wichita Wings in the first game of the 1980-81 season. When Van Eron returns from injury, the battle for the starting job begins anew. But Dowler’s taste of success boosts his confidence. He’s no longer the timid Dowler of Newport County.

Back-to-back games in San Francisco and Cleveland settle the question. Dowler registers two shutouts in a row. In the MISL, shutouts rarely happen. It takes the Kansas City Comets four seasons and 157 games to record the team’s FIRST shutout. The previous record for consecutive shutout minutes was just under 82. Dowler records almost 141 consecutive minutes of shutout time.

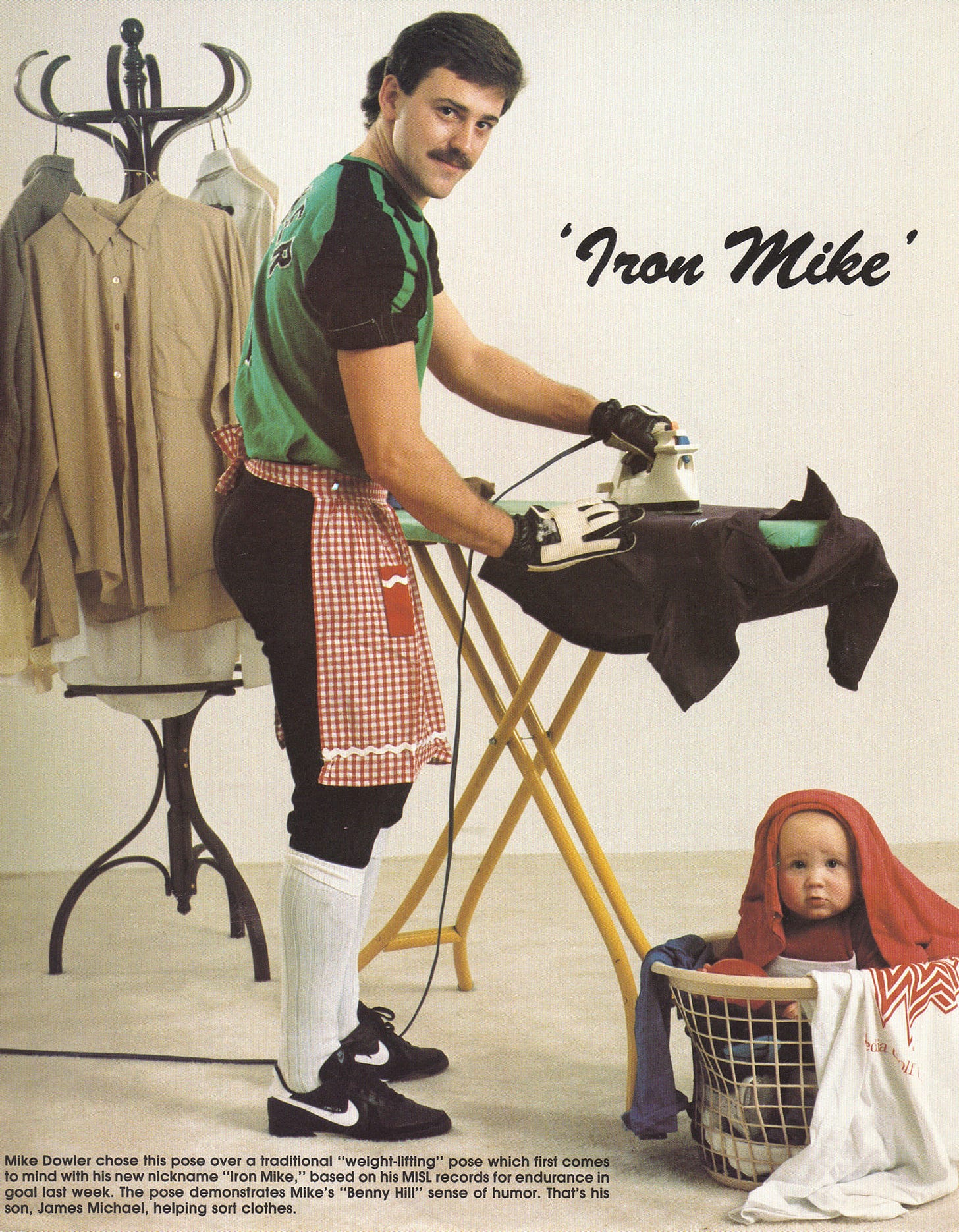

Other Wings players come from Manchester United, Chelsea, Derby County, Leicester City, Liverpool, Bolton, Everton, Sheffield, Nottingham, and Queens Park. But he is no longer Mike Dowler of lowly Newport County. Some reference the shutouts and call him “Double-0” Dowler. Others prefer "Iron Mike” Dowler. But to everyone in the MISL, he is now known as: “starting goalkeeper.”

European pros (including a few past their prime) from the Bundesliga and the English Premier League flock to the other MISL teams as well. English accents echo off the boards. When the NASL closes shop in 1984, the trend accelerates. The MISL is now the highest level of soccer in North America.

And boy is it different from back home in Europe. Pop anthems echo throughout the arena. Cheerleaders and dancers prance about. Play stops for TV timeouts. The offside rule is terminated. A draw is a thing of the past, eliminated by overtime and, if necessary, a shootout. The purists are outraged. Outraged! Real soccer doesn’t have timeouts! The clock shouldn’t run down, it should count up! But for now, there is nothing they can do. Professional outdoor soccer in America is dormant.

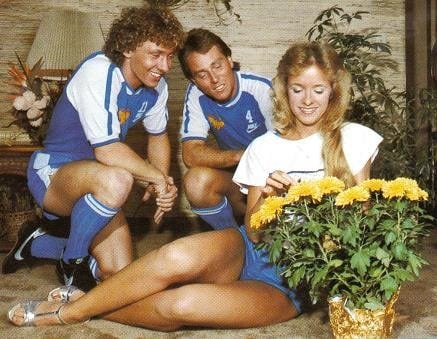

It’s the early 1980s, so the shorts are SHORT. Thigh muscles bulge out.

“Other muscles too,” says Terry Nicholl.

Fake-baking is all the rage.

“My players all look like they just came back from a damned vacation,” says Wichita coach Roy Turner.

That’s thanks to Nicholl. He opens up Sun-Tana on the east side of Wichita. Dowler’s wife Elaine grabs a part-time job manning the tanning beds.

There is no legacy fan base, so each team has to create one from scratch. Grandpa didn’t take dad to see the Kansas City Comets back in the day. MISL PR director Doug Verb proudly proclaims they are the first professional league to hit 40% female attendance. Grandma, mom, and daughter are all learning the game together. The players are learning it along with them.

“Often, the first game they’ve ever seen, they play in,” Wichita Eagle-Beacon reporter Tom Shine quips.

And the teams are learning how (and how not) to market it. Ten cent beer night goes awry (predictably?) in Wichita as sheriff’s deputies scamper from fight to fight across the Kansas Coliseum. But the teams that prosper invent new and innovative ways to promote the game: laser lights, celebrity appearances, promotional gimmicks. The NBA watches and learns. Go to a Lakers or Timberwolves game today to see the result.

Moosehead, the Croatian Cueball, the Tackling Scot, Andy Scores, The Danish Cowboy, Mooch, The American Dream, Budgie, Tricky Dickie, The Canuck, 18 Karat, Supergnat and Chugger: even the nicknames are wild. English players make up a plurality of the league’s rosters, but the Yugoslavs are a disproportionate number of the top players. And the topmost is the “Lord of All Indoors,” Slaviša “Steve” Žungul, star of the New York Arrows.

Described by a Wings staffer as “looking like he’d been hit in the head with a skillet,” Žungul is an unlikely star. His receding hairline is accompanied by long, stringy hair in back. Banned from outdoor play by FIFA after defecting from Yugoslavia, Žungul dazzles indoors. In the 1980-81 season he scores twice as many goals as the second-leading scorer in the league.

Fellow Yugoslav Srboljub “Stan” Stamenkovic (you’d go by Stan too) picks up three league MVP awards despite a belly that confirms his nickname: the Pizza Man. When it comes to health and conditioning, the European players of that era have a more relaxed standard. One team bans cigarette smoking in the showers (the inevitable result of banning smoking in the locker room). Danish star Jorgen Kristensen lives off a diet of “Bud Light and no eating,” says Terry Nicholl. Hyperbole and Bud Light aside, Kristensen is so nimble that in his home country of Denmark it is said that he can get past you inside a telephone box.

Mike Dowler’s life changes. The Wings, in true MISL fashion, capitalize on Dowler’s newfound celebrity. They sell countless “Dowler Saves” license plates. Team sponsor Subaru gives Dowler a car adorned with his name and the Wings logo (don’t park at the strip club!). TV interviews after the game become de rigueur. His name runs in stat lines on newspaper pages across the country.

“I remember being out to dinner with my family, being asked for autographs. My wife would say, ‘Yes, he doesn’t mind, but can he finish his dinner first?’” Dowler remembers.

Fans stop him in the street and ask him if he’s THE Mike Dowler. He now realizes he is a role model, whether he likes it or not. The strange new rituals of indoor soccer grow on him.

“Suddenly you have raucous music, cheerleaders, the crowd are into it, you have Krazy George beating his drum. You get into the atmosphere…It was rockin’,” says Dowler.

Six shots on goal is a busy day outdoors. Dowler regularly faces 40 indoor. Unlike the outdoor game, with its enormous field, he is almost always in the action. It takes a toll.

“My elbows were a right mess. I had sacks of fluid the size of golf balls,” Dowler says.

No goalkeeper jersey has elbow pads big enough. The trainers create a pad of reinforced foam to keep the elbow-draining to a minimum.

The Wings corner the market on Danes. Jorgen Kristensen glowers his way to the top of the assists board in the league (“He had a bit of Hamlet in him,” says Wings beat reporter Tom Shine.) The Wings sign Kim Røntved and his brother Per, captain of the Danish national team, Erik “the Wizard” Rasmussen, Frank Rasmussen…SIGN EVERYONE NAMED RASMUSSEN.

Danish flags flutter in the crowd as the boys from Copenhagen dance around the field. The Wizard’s precise footwork entrances opposing players, who fall down to the turf in threes and fours, as if in obeisance to his skill.

In the crowd, it’s boots and suits. Aircraft workers on the line at Boeing, Cessna, Learjet, and Beech aircraft sit alongside their bosses to cheer on the Wings. The team color, orange, is the new black. Tickets become hard to get after a few seasons. All 9,868 seats sell out dozens of times. The access to the players is extraordinary for a major league sports team. After the game, you can have some beers with the boys down at the Hatch Cover Restaurant and Bar. If you want to stay up late, head to The Cowboy nightclub and dance the night away with Frank Rasmussen. But you probably won’t see the team’s Welsh goalkeeper out late. His priority is a baby boy named James Dowler. The little fella enters the world in Wichita, KS at St. Joseph’s Hospital. A couple becomes a family.

[TO BE CONTINUED NEXT WEEK IN PART 3 OF 3 OF “THE LOST LEAGUE”]