Generation Zero - The MISL: A View From a Soccer Traditionalist - Part 1/2

An excerpt from Chapter 8 of Hal Phillips' book about the rise of the US National Team in the 1990s

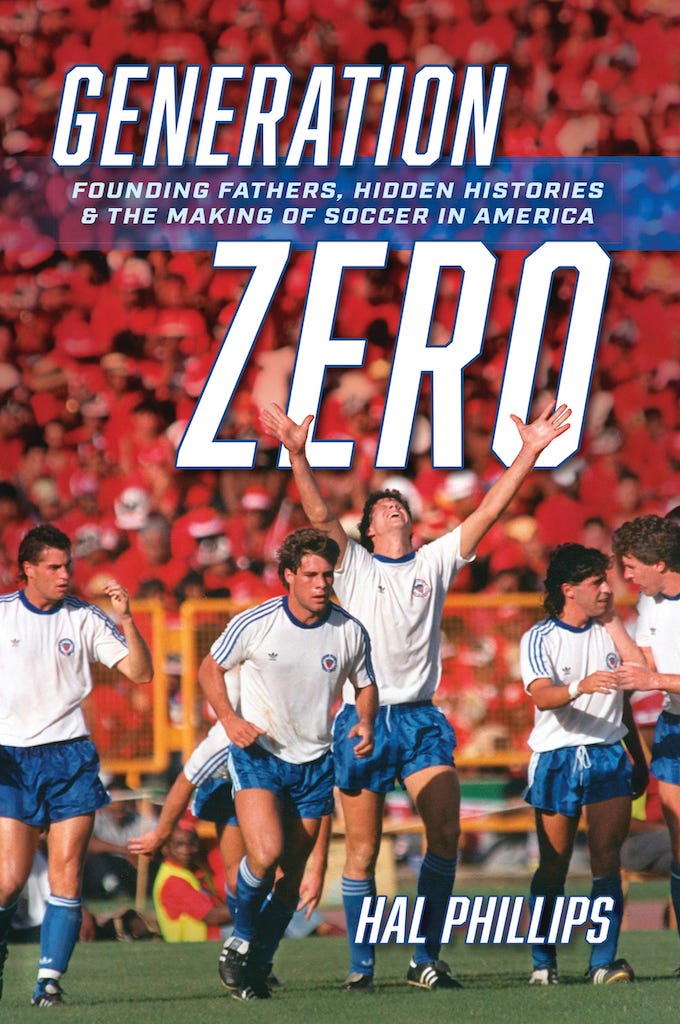

For the next two weeks, we pass the typewriter over to Hal Phillips, author of Generation Zero: Founding Fathers, Hidden Histories & the Making of Soccer in America. What follows is Part 1 of an excerpt from Chapter 8, which focuses on the MISL. Phillips’ perspective, that of a soccer traditionalist, is a valuable one for those of us who are indoor soccer-centric. If you like this excerpt, go buy the book here! And if you’d like to learn more about Hal Phillips, click here!

From Chapter 8 of Generation Zero, by Hal Phillips:

Twenty-first century U.S. soccer fans may not realize it — or wish to contemplate such an unbecoming reality — but for a short time immediately post-NASL, indoor soccer was the American game’s dominant professional strain. Indeed, the heyday of Major Indoor Soccer League (MISL) took place during this period, even as the country’s first golden generation of outdoor talent began to coalesce. These coincidental facts, these uncomfortable truths, represent yet more indicators of a domestic soccer culture in a worrisome state of inconstancy, if not outright crisis.

However, even outdoor purists were obliged to acknowledge that the MISL had survived into 1985 and beyond, while the North American Soccer League (and the second-division American Soccer League) had not. The pay wasn’t spectacular indoors, but the checks frequently failed to bounce. What’s more, the matches were actually on TV at that time, filling late-night space next to competitive lumberjacking on ESPN.

In 1986, MISL’s newest expansion franchise, the New York Express, named Ray Klivecka head coach and player personnel director. He had this to say when 1985 Hermann Trophy winner, Duke’s Tommy Kain — the top Express draft pick that winter — chose not to report.

“I was counting on Tom this year,” Klivecka told the Chicago Tribune. “His decision came out of left field. I knew his dream was to be an outdoor pro, but I thought that wasn’t in the picture . . . He’s losing a year in the MISL, but I told him that if it didn’t work out, he could come back, even this year. He’s welcome. He has the potential to be a good indoor player. That’s where the game is in the U.S., and that’s probably where his future is.”

Klivecka had a clear business interest in the Express and its fortunes, but he was not some wild-eyed indoor-soccer evangelist. He’d been an outdoor footballer all his own life, as an all-American at Long Island University, as an assistant to Angus McAlpine in training U.S. Soccer Federation youth squads during the late 1970s, as an assistant to Cosmos coach Eddie Firmani for two years. No one knows whether Klivecka honestly preferred the indoor game, or not — but he clearly sensed where the U.S. soccer winds were blowing during the mid-1980s.

Better than most, the coaches understood how shaky NASL truly was. When Klivecka had the opportunity to join the ownership group behind the MISL expansion franchise in St. Louis, he jumped at it: The Steamers joined MISL for the 1979-80 season. He would briefly lead the NASL’s Rochester Lancers in 1980, but that was his last outdoor gig. He coached the MISL Buffalo Stallions for two seasons before rejoining the Cosmos, in 1984-85, as head coach for their first (and last) indoor season. The following summer, he joined the expansion Express.

So, Klivecka wasn’t posturing for the Tribune reporter. He was voicing an attitude toward indoor soccer — “That’s where the game is” — that proved quite pervasive, if not exactly prevailing, in 1986. Having watched NASL fold, having seen no replacement outdoor league forthcoming, a lot of people felt indoor was the way forward for soccer in this country.

The Express would eventually help illustrate why they were mistaken.

MISL had awarded the new franchise to financiers Ralph McNamara and Stan Henry, who intended to generate the club’s initial operating capital from an issuance of public stock — the kind of market-based, true-believing thing people did during Reagan’s go-go Eighties. They had partnered with none other than former Cosmos keeper Shep Messing, who would play goal and serve as the face of their franchise.

The Express positioned itself as an all-American response to the New York Arrows, the demonstrably ethnic MISL franchise it replaced on Long Island. Messing had played six winter seasons for the Arrows. He quickly lined up former teammate Ricky Davis, whose Steamers contract had played out. He also recruited former Cosmos Mark Liveric, Hubert Birkenmeier and Andranik Eskandarian.

“The whole plan for franchise success was built around Ricky Davis. Not the greatest player at that point, but the one with the great American-born name, demeanor and name recognition,” Micah Buchdahl told the website FunWhileItLasted.net, a treasure trove of fascinating information about failed sports leagues and franchises of all kinds. Buchdahl served as director of public relations for the Express.

A few days before the media event introducing Davis, “I was told [Ricky] had changed his mind,” Buchdahl told the site. “We had announced that we would introduce the top American-born player in soccer. I remember [Express GM] Kent Russell and Shep asking me if it would be a problem if we just said we had meant Kevin Maher.

“I told them we’d be totally screwed.”

By January 1987, not even halfway through the club’s maiden campaign, it was all coming apart. Russell and his assistant bailed on the Express first — jumping to the Dallas Sidekicks. Buchdahl, just 24, became acting GM. Then, on Feb. 1, 1987, the club failed to pony up $75,000 in player payroll, forcing the league to draw down the club’s $250,000 letter of credit to cover it. The owners pulled the plug two weeks later, initiating Chapter 11 proceedings. Let the record show the Express finished 3-23. For those three victories, they spent a reported $3 million during just nine months of operation. Buchdahl ended up holding much of the club’s office equipment hostage in his aunt’s garage — in a failed effort to wangle five weeks of back pay.

“This team should never have been let in,” Eskandarian told the Chicago Tribune. “I don’t think the league is going to last long if it’s going to be like this.”

For Shep Messing, a childhood hero to Generation Zero and one of the highest-profile U.S. players of the 1970s, the Express debacle was an ignominious close to a colorful, hyper-eventful on-field career. If there was a better embodiment of “Seventies Boomerdom, Pro Soccer Division” than Shep Messing — born in 1949, Harvard Class of ’72 — I can’t identify him.

When something happened during this consequential era of American soccer, Messing was there in the thick of it. Between the pipes for Pelé’s two finest seasons in New York (1976 and ’77), Messing had also been in goal the year before — for the Boston Minutemen — when fans stormed the field and literally ripped the shirt from The King’s back. By then, as a U.S. Olympian, Messing had experienced firsthand one of the decade’s mind-bending tragedies: the kidnapping and killing of 11 members of Israeli’s Olympic team during the Munich Games in 1972. This tragic, macabre drama had unfolded just 30 yards down the hall from Messing’s dorm room.

“It really forged a greater Jewish identity for myself at that moment than I ever had before,” he told The Guardian in 2015. “That was a turning point in my life as an athlete — and as a Jew. Words really can’t describe it.”

Eighteen months after the Olympic experience, Messing latched on with the Cosmos. He was promptly kicked off the team for posing nude in Viva magazine, for a reported fee of $5,000. Management argued he’d violated the morals clause in his contract; Messing asserted he’d delivered the club more exposure than anything in franchise history.

He signed with Boston for the ’75 NASL season. Pelé arrived in New York at the same time. The Cosmos re-signed Messing a year later, his trademark mop of curly brown hair and pornstache in tow. He cut a figure straight out of Boogie Nights — something even Harvard graduates could pull off during the 1970s, apparently.

Not yet 30, Messing landed with the newly relocated Oakland Stompers in 1978. There he found time to publish his freewheeling autobiography (The Education of an American Soccer Player) before joining the Rochester Lancers in ’79, his final outdoor season. That was the Express connection: The MISL Arrows of the early 1980s were stocked almost entirely with NASL Lancers.

Like so many Boomers, Messing transitioned straight from the self-actualizing Seventies to the blindly capitalist Eighties. It didn’t go well. Though Messing’s expansion misadventures with the Express registered barely a ripple in that era of soccer anonymity, white-collar crime, junk bonds, and savings and loan crises. Come the Nineties, Messing moved seamlessly into the broadcast booth.

As for McNamara, the moneyman behind the N.Y. Express, his firm closed down when the stock market tanked in October 1987. Four years later, New York state revoked his broker’s license. In the late 1990s, he surfaced in Florida under the name Ralph DeLuise, operating what proved to be a fake venture capital operation. In 2007, a court found McNamara guilty of racketeering, conspiracy to commit racketeering, communications fraud, grand theft, loan broker fraud and money laundering. He was sentenced to 15 years in federal prison.

(TO BE CONTINUED NEXT WEEK)

Coming Next Week: Part 2 of Generation Zero - The MISL: A View From a Soccer Traditionalist

If you like this excerpt, go buy Generation Zero here!